The more I examine the symptoms and apparent causes of Addictive Personality Disorder, the more I think all of us, at some level, demonstrate addictive habits.

Last year someone told me that I had an Addictive Personality Disorder. I immediately dismissed it because, though I did have trouble with alcohol in my younger days, once I decided to quit drinking, I had no trouble at all in doing so. What I did not realize is that my addiction to alcohol—even though I didn’t know I had it—was then replaced by another addiction. It’s obvious to anyone who looks at me that one of my comforts is food.

I have a good friend who had trouble with drinking and he got control of it and has been sober for, as far as I calculate, 20 years. Perhaps more. He once told me that he noticed that almost every person in his “meetings” drank coffee in excess and smoked so many cigarettes that he, a smoker, could hardly stand it. He was clearly telling me that he saw one addiction simply being replaced by another.

I have a good friend who had trouble with drinking and he got control of it and has been sober for, as far as I calculate, 20 years. Perhaps more. He once told me that he noticed that almost every person in his “meetings” drank coffee in excess and smoked so many cigarettes that he, a smoker, could hardly stand it. He was clearly telling me that he saw one addiction simply being replaced by another.

One of the leading factors of the addictive personality is that we look outside of ourselves for comfort, for some relief from our stresses or unhappiness. For myriad and infinitely varied and individually personal reasons, we are unhappy. Unhappiness comes in many forms and, depending on the level of our self-esteem or magnitude of our self-loathing, it can manifest in guilt and shame that we carry with us wherever we go.

It’s So Easy!

Author and Buddhist nun, Pema Chödrön, once offered an example of how easy it can be to create an addiction. She said (I’m paraphrasing), “Make time for yourself every night to have a warm, relaxing bath…” She asked her seminar attendees to imagine how that felt. She continued, “Now, make that time for yourself every evening for two weeks. Imagine that. Now, on the next evening, don’t take that bath.” Her comments were met with laughter. Her example demonstrates how easy it is for us to become dependent on behaviors that can lead to addictive behavior. If we get used to that bath being the thing that calms us, without it, we cannot relax.

Author and Buddhist nun, Pema Chödrön, once offered an example of how easy it can be to create an addiction. She said (I’m paraphrasing), “Make time for yourself every night to have a warm, relaxing bath…” She asked her seminar attendees to imagine how that felt. She continued, “Now, make that time for yourself every evening for two weeks. Imagine that. Now, on the next evening, don’t take that bath.” Her comments were met with laughter. Her example demonstrates how easy it is for us to become dependent on behaviors that can lead to addictive behavior. If we get used to that bath being the thing that calms us, without it, we cannot relax.

Looking outside of ourselves for anything is the foundation of addictive behavior. As humans, it begins in our infancy. We have to look outside of ourselves to our mother for care. Our basic needs must be met by another. As we grow, it extends beyond basic care to seeking approval from our parents. If we behave as they wish us to, we get love and approval. So, as we grow, we keep focusing on something outside of ourselves for love and comfort and approval. With that beginning, it is not difficult to understand how we can keep looking outside of ourselves for love and comfort as we grow to become adults.

As we grow and experience the pains and difficulties of human life, we also begin to look outside of ourselves for comfort. We look outside of ourselves for love and approval so it’s only natural that we look outside of ourselves to ease the unhappiness we feel when we’re not getting it. Look around you. How many people do you know who, to ease their pain(s), seek temporary comfort in the next drink, the next pill, the next substance, cookie or orgasm?

As we grow and experience the pains and difficulties of human life, we also begin to look outside of ourselves for comfort. We look outside of ourselves for love and approval so it’s only natural that we look outside of ourselves to ease the unhappiness we feel when we’re not getting it. Look around you. How many people do you know who, to ease their pain(s), seek temporary comfort in the next drink, the next pill, the next substance, cookie or orgasm?

And then we come to crave that momentary relief, we come to need that momentary relief, we come to be addicted to that momentary relief. For many, it’s the only pleasurable thing in their life.

But There’s More!

Another challenge of dealing with being an addictive personality is being in a human body that works on electro-chemical impulses. Science is discovering that we can become addicted to our own chemicals. Studies have shown that gamblers, for example, become addicted to the adrenaline released with the thrill of making a wager. As with most illicit drugs, our body gets used to assimilating the adrenaline and the gambler needs to make larger and larger wagers in order to release larger amounts of the adrenaline the body now needs. The gambler becomes addicted to his own adrenaline. And the addictions to our own chemicals apparently is not limited to such thrilling ones like adrenaline.

A woman from my weekly meeting recently said she was at a seminar where the presenters said our bodies also get used to the chemicals released by our ordinary moods. They were postulating that if, for example, you are predominantly an angry person, then your body becomes used to the chemicals your body releases when you’re angry. Their conclusions being that we become used to living with a specific mood and our body becomes addicted to those associated chemicals. It thinks that is the normal way to feel and expects those chemicals. So, on some level, it feels good to be angry. It’s what the body knows and expects.

Interestingly, just the previous week, I had been trying to smile more. I have never been one to smile much at all. Yes, some things can make me laugh and I have, on rare occasion, laughed to tears. But, among even my best friends, I am known to always have a straight face. When zinging funny lines back and forth, I nearly always have a straight face. Perhaps part—maybe most—of that was learned. You know, it’s funnier to deliver a funny line with a straight face, so, in my youth, I practiced that. But, perhaps because of my own training, here in my old age I have discovered that I rarely smile.

I’ve heard it said that, “…we don’t sing because we’re happy. We’re happy because we sing.” I have also heard that we can change our mood into a happy one by smiling. One study said that they had people put a pencil across their mouth, thereby raising the corners of the subjects’ mouths. Their results were that people we’re happier even when they mechanically created a smile.

I’ve heard it said that, “…we don’t sing because we’re happy. We’re happy because we sing.” I have also heard that we can change our mood into a happy one by smiling. One study said that they had people put a pencil across their mouth, thereby raising the corners of the subjects’ mouths. Their results were that people we’re happier even when they mechanically created a smile.

Recently, I was reading a book by Lizzie Velsaquez, an incredibly inspirational young woman. I was imagining that someday I would get to meet Lizzie and I smiled. I felt a warm glow physically move down the back of my neck and spine. The smile brought a tingling joy to my body.

Pondering the feeling later, I thought about, not just the emotion of joy I experienced, but how wonderful my body felt from the physical sensation of smiling. The smile had released some chemicals within me and they gently caressed their way through my body. So, in the interest of science and my history of sullen moods—or, at least, facial expressions—I decided to conduct an experiment. I made myself smile again. The result surprised me. Though not as intense as when I was imagining meeting Lizzie, the smile on my face again caused me to feel good! I smiled for, perhaps, ten seconds. I felt good. Maybe I was on to something! More than just some cliché or platitude, I smiled and felt happy. Hmmm…

Pondering the feeling later, I thought about, not just the emotion of joy I experienced, but how wonderful my body felt from the physical sensation of smiling. The smile had released some chemicals within me and they gently caressed their way through my body. So, in the interest of science and my history of sullen moods—or, at least, facial expressions—I decided to conduct an experiment. I made myself smile again. The result surprised me. Though not as intense as when I was imagining meeting Lizzie, the smile on my face again caused me to feel good! I smiled for, perhaps, ten seconds. I felt good. Maybe I was on to something! More than just some cliché or platitude, I smiled and felt happy. Hmmm…

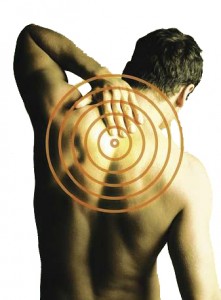

I waited a few moments, and then I smiled again. Again the feeling of happiness permeated my body. OK. Next step. I decided to keep the smile on my face for as long as I could. After about ten or 15 seconds, it began to hurt. And it didn’t hurt at the corners of my mouth as you might suspect (especially if I were making a joke about unused or long-neglected facial muscles). There was a pain between my shoulder blades! I dropped my smile and the pain eased. After another few moments I again tried a prolonged smile. First the tender embrace of endorphins poured down my spine. Then that cramping, almost knife-like stab between my shoulder blades appeared again.

I waited a few moments, and then I smiled again. Again the feeling of happiness permeated my body. OK. Next step. I decided to keep the smile on my face for as long as I could. After about ten or 15 seconds, it began to hurt. And it didn’t hurt at the corners of my mouth as you might suspect (especially if I were making a joke about unused or long-neglected facial muscles). There was a pain between my shoulder blades! I dropped my smile and the pain eased. After another few moments I again tried a prolonged smile. First the tender embrace of endorphins poured down my spine. Then that cramping, almost knife-like stab between my shoulder blades appeared again.

I wondered if I was so used to not smiling, that my body didn’t like it. Now I was in my meeting and this woman was relaying some information from a study that said we become addicted to our own chemicals; the ones we secrete the most often are the ones with which we become accustomed, even to the point of addiction. Sad people stay sad because their bodies want the chemicals. The same for angry people and happy people and, well, you name it. Is it possible that more than a half century of not smiling has caused my body to crave chemicals associated with, let’s say, sadness? Why else does it hurt my back when I attempt to hold a prolonged smile?

A Battle on More than One Front

I know that the answers to my own happiness (or whatever my needs) cannot be found outside of me. They will not be found in a new car or a bigger house or a relationship. I create my emotions. No one puts them into me. I create my joy and sorrow. I decide what makes me happy and what will not. So, therefore, it is nothing that is outside of me. But, besides the conditioning we, as humans, have from birth to look outside to have our needs met, I now find that our bodies become used to certain chemical cocktails. So, in my desire to live a happy life, not only am I battling life-long conditioning, I am battling a life-long addiction to my own chemicals.

I know that the answers to my own happiness (or whatever my needs) cannot be found outside of me. They will not be found in a new car or a bigger house or a relationship. I create my emotions. No one puts them into me. I create my joy and sorrow. I decide what makes me happy and what will not. So, therefore, it is nothing that is outside of me. But, besides the conditioning we, as humans, have from birth to look outside to have our needs met, I now find that our bodies become used to certain chemical cocktails. So, in my desire to live a happy life, not only am I battling life-long conditioning, I am battling a life-long addiction to my own chemicals.

And, if I can get a handle on this—learn to force myself to smile past my own (literal) back stabbing—what challenge will I next discover?

It takes an effort to remain mindful of who we are and what we desire and the choices we make. We’re fighting patterns and habit and addictions of which we are not even aware.

I believe that, ultimately, we’re all looking for love. What we do not realize is that we already are that love. Everything we need is within us. Love comes to us from our Creator. We can best feel it by sharing it. Being mindful of that is helping me to overcome the chemical reactions within my body.